Thoughts in Semi-Solitude

With apologies to Thomas Merton

The first chapter of Leanne Shapton’s Swimming Studies is a perfect paragraph. It’s titled “Water.”

Water is elemental, it’s what we’re made of, what we can’t live within or without. Trying to define what swimming means to me is like looking at a shell sitting in a few feet of clear, still water. There it is, in sharp focus, but once I reach for it, breaking the surface, the ripples refract the shell. It becomes five shells, twenty-five shells, some smaller, some larger, and I blindly feel for what I saw perfectly before trying to grasp for it.

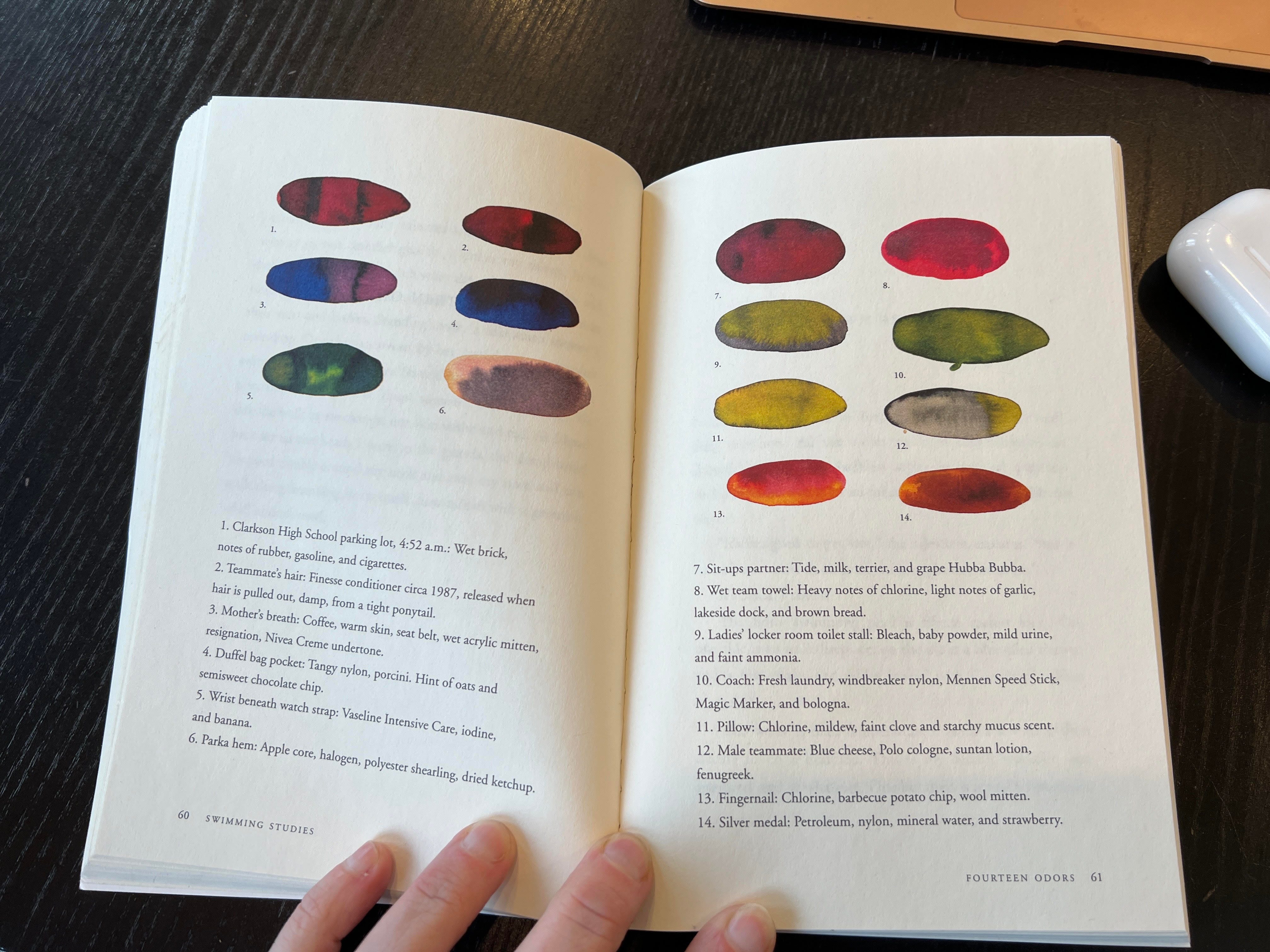

The chapters that follow are generally longer, though vary in length and include actual sketches amid spare autobiographical vignettes of Shapton’s adolescence as a competitive swimmer and reflections on how that formation still shapes her life. Her descriptions—especially of smell—are remarkably vivid and perhaps point to her talents as an illustrator as well as an author. It’s as though her capacity for observation is multiplied by the mediums in which she works.

I especially love the opening image of the shell because it’s a neatly coiled introduction to both the theme of the book, and also it’s structure. The refraction evokes her approach to the book—a pointillistic memoir that jumps back and forth in time based on personal associations and sense memories. In less skilled hands it could be disorienting, but instead her narrative leaps illustrate how one thing—swimming, a shell—can have a kind of kaleidoscopic influence on our lives.

It’s also true that rarely have I seen my own experience of trying to write memoir and personal essay so clearly described. I know what I want to say only until I sit down at my laptop and start typing. Until I break the water’s surface and reach for the shell I could see so clearly a moment ago. Then suddenly the thing I want to say becomes obscured by countless other things that also seem relevant, urgent even. Maybe one of them is the real shell? You don’t know until you try to touch it. Which is time consuming and maybe a little dispiriting when your hand comes up empty over and over again. But I find Shapton’s work a beautiful reminder of what’s possible if you keep feeling around.

Which is what I’ve been up to for the last month. Yesterday I wrapped up a sabbatical of sorts, an extended writing and reading retreat that I negotiated when I accepted a new position as an acquisitions editor for Eerdmans last fall. It was unpaid of course, but still a huge privilege to have the means and supportive colleagues to pull it off. I holed up at a friend’s empty house in rural Michigan with a frozen lake outside my window and tried to reconnect with my own writing practice after a season during which navigating Covid’s mercurial demands—both in my personal and professional lives—zapped all my creativity.

I also swam a lot while I was away. The little town I was in had a community rec center with a large pool that they share with the high school swim team. Most days I took a break around noon and headed down to join the others also taking a break to get wet in the middle of the day in the middle of winter. Among them a woman with gray hair and bright eyes when she spots a new person. In the shower she explained to me that she and her husband drive into town together and he does the grocery shopping while she swims. This seems like a very nice arrangement to me.

Also among the swimmers I met is a woman who spends a full two hours in the pool almost every day on top of cycling, jogging, and weightlifting on the regular. She’s the mother of five, the youngest of whom is in high school, and hit four miles in one of our early swim sessions together. In contrast, I’m usually in the pool for under an hour and have to push hard to hit a mile during my longest swims. But this is one of the things I love so much about swimming—it meets you where you’re at with the invitation to both enjoy and challenge your body. People with widely varied athletic abilities can enjoy it together, swimming side by side.

This midday swim was my most dependable social contact during my sabbatical. Though, admittedly, the same could be said for many weeks during Covid after the gym opened up again, days working from home punctuated mostly by laps and locker room conversations. But still, this break has been refreshing and I’m emerging with 100 handwritten pages, a working outline, and a clearer vision for how to move this book project forward when I’m back to writing on the side of a day job that I love enough to let consume a lot of my life.

I also read a ton over the last month (including re-reading Swimming Studies for the umpteenth time) and will be sharing some of passages that stuck with me on Instagram in coming weeks. And while I doubt this newsletter will ever become anything like a regular publication, don’t be surprised if I’m popping up in your mailbox a bit more than usual in the near future. After all, writing begets writing.

Thanks for reading.

Tonight: the 2022 L’Engle Seminar

One of my favorite projects during my time at Image was helping to launch the L’Engle Seminars. And so it’s a wild honor to be invited to speak—alongside Paul Elie and Vinson Cunningham!—as part of the 2022 seminar series titled A Digital Body: Fostering Communion and Community Online. My event is tonight at 5pm eastern. Details below. Join us!

In The Irrational Season, Madeleine L’Engle writes about being bedridden for six weeks after a bad fall, and the house full of companionable visitors who stayed with her: “Anybody who was up in the early morning felt free to come in while Alan celebrated Communion; anyone who felt like sleeping in was free to sleep. And I was part of the Body, not isolated by being shuffled off in bed, but a full part of the community.”

For people of faith, the nearly two years of the pandemic have affirmed our longing to be “part of the Body”—for that sense of companionship and community. In her time, L’Engle too was aware of the fragility of this sense of fellowship. In A Circle of Quiet, she writes: “Marshall McLuhan speaks of the earth as being a global village, and it is, but we have lost the sense of family which is an essential part of a village.”

Without a sense of others as family, our global village becomes a troubling place: we can be electronically and digitally connected while remaining spiritually and emotionally disparate. McLuhan’s spiritual vision of worldwide communion offers us a way to turn the metaphors of online existence—the “web,” social media, and more—into a foundation for fostering community. The pandemic has forced us to confront the fractures in our communities, digital and otherwise—and have revealed a need to cultivate a sense of family that goes beyond parish, church, and school walls.

In this four-week online seminar, writer and teacher Nick Ripatrazone will lead a conversation on the global family in the digital age. With guests Paul Elie, Lisa Ann Cockrel, and Vinson Cunningham, he’ll talk about what it means to be “part of the Body” in an age of disembodied connection.